Cotton was King

In the Deep South, cotton was king, not only prior to emancipation, but long after. Sharecropping evolved as a way for white cotton plantation owners to have their cotton cultivated and picked by free black farmers and landless white farmers for low wages and long hours of toil. They were called sharecroppers.

Typically sharecroppers were given a plot of land to work. In exchange for the privilege of using the land, they owed the landowner one-half of the profits at the end of the season. The owner provided the tools and the farm animals. The sharecroppers had to purchase the rest–the seed, tools and fertilizer–and planted their own small gardens. But, while waiting for Settling Day at the end the season, the families often needed help with food and clothing, which was procured on credit from a local merchant or from the “company store”–a store on the plantation itself–all at inflated rates.

On Settling Day, these purchases were deducted from the sharecroppers’ half of the profit. Not surprisingly, the books were often rigged in the landowners’ favor so that the sharecropper was shown to OWE money at the end of a long season. This left many sharecroppers in perpetual debt, tying them to the owner and the land.

Cotton was extremely labor-intensive. Work began in March to break up the soil, running “Middle-busters” over it to form furrows and mounds. In May, sharecroppers would dig narrow trenches in the mounds and drop cottons every 18″. As the plants sprouted in Spring, the grueling task of chopping began, working down the rows with long-handled hoes to cut back weeds from the tender cotton plants. This job fell to children as young as 6 years old. The heat was stifling and the sun pounding. Bugs, especially mosquitoes and flies, were rampant and cabins were often smoked or sprayed to drive off flies, shuttering windows for the night.

Early in season, light-hued blossoms would appear. These would darken and wilt, falling off in about three days. Pollination would occur. Soon the tiny green pods would form at the base of the flower.

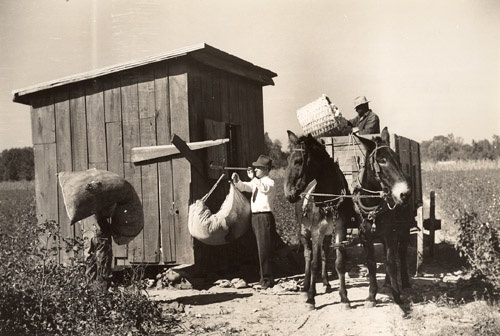

By July or August, these pods would swell into a bolls–seeds wrapped in willowy fibers. By late August the bolls would split, turning the fields into a sea of white. Stooped or on their knees, the sharecroppers would work their way down the long rows, using one hand to plunk the cotton from its spiky clutch; the other to stuff into a long white bag draped over their shoulders. Some sacks had tar on the bottom to help them slide more easily along the ground. A bag held 100 pounds of raw cotton. A good picker could pick 100 pounds by lunch and another 100 pounds by the end of the day. Fields required several passes as the cotton did not ripen at the same time.

A typical yield was 1500 pounds per ten acres, which translated into 500 pounds of ginned cotton or ten bales. In 1918, cotton was selling at 30 cents a pound.

Settling Day usually took place in late November. With many blacks illiterate, and with the whites not believing figures even if a black man had the ability to kept track, many sharecroppers were taken advantage of.

In 1917-1918, this left sharecroppers with very few choices: to move to another plantation in the hopes of finding a more honest overseer; or to move north, often in the dead of night to avert detection. (See the April 3 Blog on The Great Migration.)

Cotton plantations continued to need large labor forces to hand-pick cotton until the rise of harvesting machines in the 1950s, virtually eliminating the need for manual cotton labor.