Packinghouse workers in the early 1900s endured hot, loud and dangerous conditions. Irregular working days swung wildly depending upon live animal shipments and production needs. On Mondays and Tuesdays, when cattle shipments typically arrived, sometimes working days stretched from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m. or midnight. Summers were a lull period where layoffs were many. Wages were low for the unskilled and injury rates ran high—the Armour plant averaged 23 accidents per day in 1917.

It was a buyers’ market. Packinghouses opened each morning to 200 – 1,000 willing workers waiting for jobs. Foremen or yards policemen went out to the gate and choose the number of workers needed that day from the strongest in the crowd. Only about 10 men in a gang of 200 were “steady time” men, guaranteed a full 6 days of pay. Many others were hired as “casual” workers, meaning that a worker might only be asked to stay the day or only a couple of hours as needed, for as low as 15 cents an hour.

(Pictured Below: Swift Beef Department Dropping Hides and Splitting Chucks 1906: Library of Congress)

The Birth of the Assembly Line

Although Henry Ford is credited with creating the assembly line in the manufacture of his Model Ts, the hog slaughterhouses of Cincinnati were the first to utilize an assembly line process as early as the 1830s.

To help speed the time-intensive slaughtering and cutting processes, the packinghouses used extreme division of labor, where each man might perform a single cut or task. Because of the odd shapes, and differing size, weight and quality of the animals, many aspects did not lend themselves to mechanization. So instead of mechanizing the process of dismantling the animals, packinghouses mechanized how the carcasses were moved from station to station. Slaughtered animals were raised with hoists, and moved along overhead rails and along conveyors. Men no longer brought the hogs and cattle to each station—the work came to them.

The all-around butcher, who had been in use as late as the 1880s, was now replaced by a killing gang of 157 men. The jobs were divided into 78 different “trades.” Each man performed his individualized task 1,000 times a day.

The time-savings were enormous. The slaughtering and hanging process that had taken 3-4 men up to 15 minutes per animal, now could be done by one “shackler” who could hoist 70 cattle carcasses each minute by clipping the shackle around the hind foot and letting steam power raise the animals up.

“Looking down this room, one saw . . . a line of dangling hogs a hundred yards in length; and for every yard there was a man, working as if a demon were after him.” The Jungle

At the Mercy of the Foreman

Packinghouses ran on low margins. The cost of the animals (the raw materials) made up 89 cents on the dollar, leaving little room for profit. Because the work could not be mechanized, the only option was to increase output. In other words, to make the men and women work faster.

In 1908, the endless chain in hog slaughtering was seen as a major breakthrough. It prevented the slowest worker from regulating the speed of the entire gang.

In 1908, the endless chain in hog slaughtering was seen as a major breakthrough. It prevented the slowest worker from regulating the speed of the entire gang.

Now, the foremen on the killing floors controlled the speed of the conveyor line with a lever—men who were incentivized to process the highest number of animals at the lowest cost or lose their own jobs. Even small changes in speed could increase outcomes and profits. The pace of the work drew the most complaints from workers.

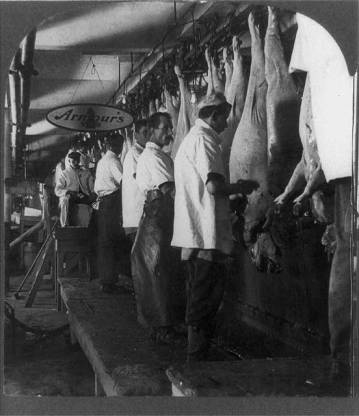

(Pictured: Armour Hog Scraping Rail 1909: Library of Congress)

The packinghouses worked to break unions and encourage constant competition. The companies established rivalries between houses within the firm and among foremen within the same house. Companies exchanged data on line speed and other factors. The fastest men were given higher paying jobs as “pacers” and were placed at critical points in the production flow, setting the pace for rest of the line. Less skilled “go betweens” were trained to fill the job above them, so positions could be filled when a skilled worker was absent for a day, and the threat of being replaced on a permanent basis kept skilled workers diligent.

“If you need to turn out a little more, you speed up the conveyors a little and the men speed up to keep pace.”A Packinghouse Superintendent

Because of the great number of immigrants and black migrants looking for work, packinghouses also had the power to break strikes. It was the strike of 1904 that brought a new group of blacks up to Chicago.

The Largest Employer of Black Workers in Chicago

Blacks’ reputation as “scabs” began with the strike of 1894 and repeated itself in 1904. During this second strike, labor agents recruited an estimated 10,000 black workers. Special trains carried black workers from Southern states and dropped them into the stockyards and alongside the packinghouses. In a single day, 1,400 arrived. As well, packinghouses brought trainloads of immigrants from Ellis Island and moved skilled workers from small rural plants.

As a whole, the blacks distrusted unions and lay their loyalties with the packinghouses themselves, though some blacks did join forces with their white co-workers in solidarity with unions. Employers went to great lengths to nurture a direct relationship with black workers through donations to black churches, Y.M.C.A.’s and the formation of black baseball teams. Though this courting did not include high wages (blacks held some of the lowest and lowest paid positions), the money was still better than many blacks could earn in their home states, especially if they were employed in agriculture as sharecroppers.

As WWI raged, the combination of plummeting immigration, white soldiers traveling overseas to fight, and the need for increased production to feed and defend U.S. and Allied soldiers, gave Southern blacks an opportunity at new and well-paying industrial jobs. Thousands traveled north to Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit, Cleveland and Evansville, Indiana.

Between 1915 and 1920, roughly a half-million blacks migrated to northern cities. The Great Migration saw Chicago’s black population burgeon. In 1890, blacks made up less than 2% of the city’s population. During WWI, the black population rose to over 100,000.

Between 1915 and 1920, roughly a half-million blacks migrated to northern cities. The Great Migration saw Chicago’s black population burgeon. In 1890, blacks made up less than 2% of the city’s population. During WWI, the black population rose to over 100,000.

The Department of Labor figures show that the number of black packinghouse workers in Chicago jumped three to five times from 1917-1918. For example, one major Chicago packing house only had 311 black workers in January of 1916, but employed 3,621 by the end of 1918.

By 1920, the Meat Trust was the largest employer of blacks, holding more than one-half of all of manufacturing jobs in Chicago’s Black Belt. The next largest employer was the steel mills, with less than one-quarter of black jobs.

In total, Chicago would gain more than 500,000 of the approximately 7 million southern blacks during the entirety of the Great Migration. By 1970, blacks would represent 33% of Chicago’s population—one-third of the city’s people.

Great Diversity

Chicago’s Union Stockyards and the surrounding slaughtering and meat-packing plants offered unparalleled diversity. More than 40 nationalities were represented, with diversity in age, gender and work experience.

The early immigrants to the trade included the Irish and German. They maintained the highest paying “knife jobs”. This was followed by Bohemians, (coming from the industrialized region of what is now Czechoslovakia), and later Lithuanians, Poles, Russians, African Americans and Mexicans.

Although they worked side by side within the packinghouses, ethnic groups rarely mixed outside of the walls of their employers, each group staying within its own ethnic neighborhoods within Chicago. This lead to great overcrowding in Chicago’s Black Belt and was one of the factors contributing to Chicago’s Race Riots of 1919.

Sources

Chicago and the Great Migration, 1915-1950; Hana Layson with Kenneth Warren; The Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom; dcc.newberry.org/collections/Chicago-and-the-great-migration

Down on the Killing Floor: Black and White Workers in Chicago’s Packinghouses, 1904-54; Rick Halpern; University of Illinois Press; 1997

Great Migration; Encyclopedia of Chicago; encyclopedia.chicaghistory.org

The Great Migration in Historical Perspective: New Dimensions of Race, Class & Gender; Edited by Joe William Trotter, Jr.; Indiana University Press; 1991

The Jungle; Upton Sinclair; Barnes & Noble Classics; 2003 (first published in 1906)

Prelude to a Riot—Irish Athletic Clubs and the Black Belt in 1919; American History USA; americanhistoryusa.com

Work and Community in the Jungle: Chicago’s Packinghouse Workers 1894-1922; James R. Barrett; University of Illinois Press; 1990

“World War I and The Great Migration”; History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, Office of the Historian, Washington D.C., U.S.; Government Printing Office, 2008.

Great information, Tamara! Thanks!

*Michelle Cox* *Author of the Henrietta and Inspector Howard series * *Web:* Michellecoxwrite (dot) com | *Tweet:* @michellecox33 |* FB: *Michelle Cox Writes

LikeLike

Thanks, Michelle. It was fascinating to learn about the packinghouses for the novel I am writing on Chicago’s Race Riots in 1919. One of my characters works at one. Thanks for reading! Tamara

LikeLike

What a scary — and dangerous — place to work. You can see why unions were formed.

LikeLike

I can’t imagine how loud, hot and dangerous these places were. And of course, no workmen’s comp if you got hurt.

LikeLike

This wwas a lovely blog post

LikeLike

Thanks Anderson for your kind words. It is hard to imagine how workers survived in those deplorable conditions. If you enjoyed my post, I’d suggest reading The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair, written in 1906. Thanks for reading and commenting!!

LikeLike