In past “Girl” best sellers, the protagonists actually were girls. Griet in Chevalier’s Girl with the Pearl Earring is a 16-year-old servant who ground paint and later posed for her master, Johannes Vermeer. In House Girl, the slave Josephine is just 17 when she plans her escape from the tobacco farm. Lisbeth Salender, the brilliant, edgy protagonist in Stieg Larsson’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo series, is 24 years old, but is under guardianship, so she and her funds are under the control of Nils Bjurman, who viscously takes advantage of her. (Don’t worry, she gets him back big-time!)

In past “Girl” best sellers, the protagonists actually were girls. Griet in Chevalier’s Girl with the Pearl Earring is a 16-year-old servant who ground paint and later posed for her master, Johannes Vermeer. In House Girl, the slave Josephine is just 17 when she plans her escape from the tobacco farm. Lisbeth Salender, the brilliant, edgy protagonist in Stieg Larsson’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo series, is 24 years old, but is under guardianship, so she and her funds are under the control of Nils Bjurman, who viscously takes advantage of her. (Don’t worry, she gets him back big-time!)

Yet, more recent best sellers use the word “girl” when actually describing grown women. Think Gone Girl And Girl on the Train.

The twisted and downright wicked Amy Dunne in Gone Girl was followed by Girl on the Train’s protagonist Rachel Watson, a drunk and lonely woman. Both women are unreliable narrators because they are, well, crazy, and not exactly women to be admired.

The twisted and downright wicked Amy Dunne in Gone Girl was followed by Girl on the Train’s protagonist Rachel Watson, a drunk and lonely woman. Both women are unreliable narrators because they are, well, crazy, and not exactly women to be admired.

The Girl on the Train title played off the success of Gone Girl. I’m in marketing, so I get it. You take a successful title and push a book with a similar title, even positioning, “If you liked Gone Girl, you’ll like Girl on the Train”. Editors, and publishers, who by the way title the books, not the authors, seem to still be riding the “Girl” train. (Sorry, couldn’t resist.)

Now Women are “Girls”

A recent trip to Barnes & Noble showed several on the “Best Seller” shelves: Lilac Girls by Martha Hall Kelly and All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda. New just this week is The Girl Who Knew Too Much, a suspense thriller/romance about a female tabloid reporter—a grown woman—investigating the murder of a starlet, who I assume is “the girl”. Only one best seller had “woman” in the title: The Woman in Cabin 10, a mystery whose female lead witnesses a murder, but is not believed because she is obviously bereaved from her recent break-up and paranoid from her apartment’s break-in.

A perusal of the bookstore shelves produced a host of “Girl” titles:

— Cemetery Girl – David Bell

— The Fireproof Girl – Loretta Lost

— The Forgotten Girl – David Bell

— The Good Girl – Mary Kubica

— The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane – Lisa See

— The Silent Girls -Eric Rickstad

— The Girl on the Cliff – Lucinda Riley

— Vinegar Girl – Anne Tyler

— White Collar Girl – Renée Rosen

So, what’s up with all the “Girl” titles? Do they simply sound better to the ear? Gone Woman certainly doesn’t have the alliteration of Gone Girl, and The Woman Who Kicked the Hornet’s Nest doesn’t exactly trip off the tongue.

Or is something more sinister at play here?

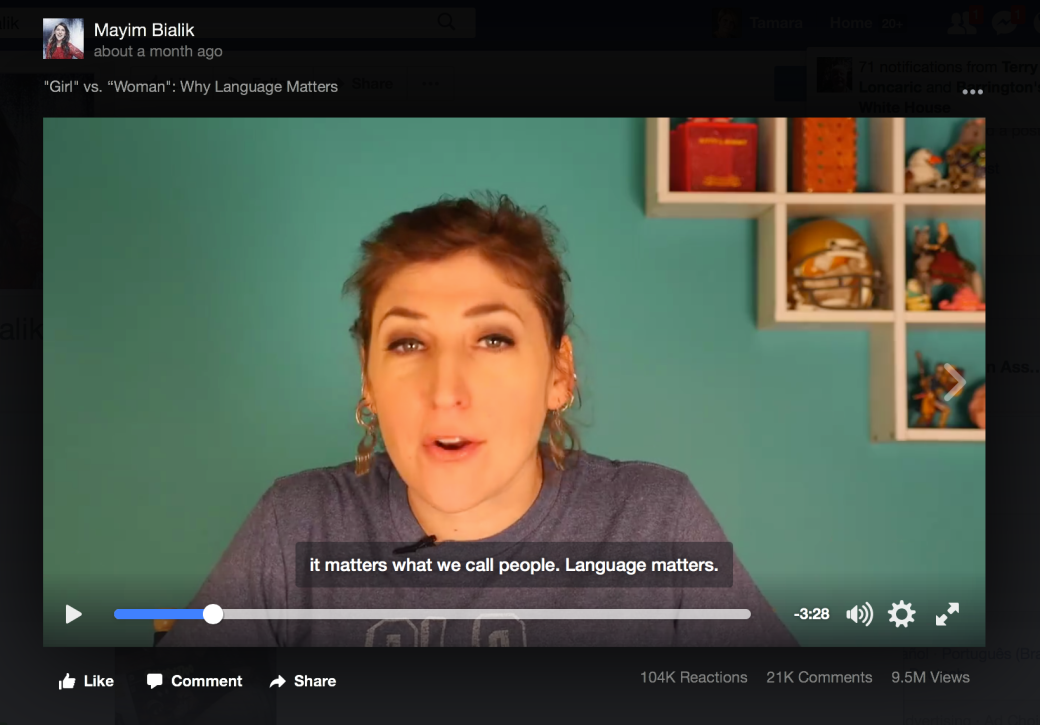

Mayim Bialik Encourages Us Not to Use the Word “Girl” to Describe “Women”

In a recent Facebook post called “‘Girl’ vs. ‘Woman’: Why Language Matters”, Mayim Bialik, of The Big Bang Theory and Blossom fame, implores women not to use the word “girl” to describe a grown woman due to the practice’s social implications:

[W]hen you use words to describe adult women that are typically used to describe children, it changes the way we view women – even unconsciously – so that we don’t equate them with adult men. In fact, it implies they’re inferior to men. Even if that’s not what most people intend, words have impact on our unconscious. Case in point: You would never say to someone: “Go ask that boy behind the bank counter if the notary is here today”.

Bialik references two scientists named Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf. Their hypothesis states, “the structure of a language determines or greatly influences the modes of thought and behavior characteristic of the culture in which it is spoken”. (Source: Dictionary.com.) So in other words, if language is biased, it’s likely your decisions and actions will be, too.

I asked if “girl” versus “women” in literature titles bothered my neighborhood ladies’ book club members. One brushed it off at first. Others gave it some consideration:

- When the book titles read Woman on the Train and The Woman with the Dragon Tattoo, then we will know that WOMEN have arrived in literature.

- Perhaps it says something about the story, or does the word “girl” trigger a different emotional response than the word “woman” and therefore attract more attention? Hmmmmm….

- I think you are right. The title Girl on a Train elicits tension, fear and danger because a girl is thought to be young and defenseless. When there is a Woman on a Train, you know that she is smart, fearless, a problem solver, and in command of a frightening situation.

We were all discouraged until that first club member, the one who’d given it much weight, made an interesting discovery. Although adult book titles may use the word “girl” in a slightly demeaning way, books for actual girls—picture books to young adult—have much more empowering characters, themes and titles.

The Children’s Section Showed More “Girl Power”

In a review of Sunday’s New York Times Best Seller lists over the past several weeks, we found this. Children’s Middle Grade included the title Women in Science, and new this week, a book called Wolf Hollow about “a small-town girl [who] is compelled to act when a new student starts to bully a veteran”. Even more encouraging, the Times’ Children’s Picture Books list contained such STEM-focused titles as Rosie Revere, Engineer and Ada Twist, Scientist, by Andrea Beaty—on the Times Best Seller list for 99 weeks and 34 weeks, respectively.

Princess is Still In

A swing through the children’s section of my local B&N did have its obligatory share of Disney princess books, but I also uncovered such books as The Big Book of Girl Power, with Wonder Woman on the cover; Ladies of Liberty by Cokie Roberts; and an “American Girl” history book called The Story of America.

Further, let’s not forgot our teen/young adult heroines. Katniss Everdeen kicks ass in the Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins, and Veronica Roth’s equally successful dystopian Divergent series features Beatrice Prior/Tris, who, as reviewed on shmoop.com, “learns how to fire a gun and beat people up”. These “girls” act like women; or perhaps, even like men.

Our Teens May Have Better Role Models Than Adults

So what are we to make of this disparity? Are we creating greater fictional role models for our daughters than we are for ourselves?

Perhaps our adult fiction needs to take its cue from the authors for children’s, middle and young adult books. To create more female characters—protagonists who are strong, smart and independent. Woman who overcome adversity. Women who control their own destiny. Women who are not called girls.

I agree! Referring to women as girls is not the best way, in my opinion, to break the ‘Glass Ceiling.’ I recently heard a song by a popular male singer that sings, “I’m in love with your body … and the shape of you.” I think this idea or attitude is hardly the message that will help elevate women to equal status and continues to focus on a woman’s self-worth connected to her physical appearance. Double messages for sure!

LikeLike

It’s not something I ever really thought about before, but now I intend to be more cognizant of using woman when speaking about one of my female friends or acquaintances.

LikeLike

Great article, Tamara. As an author of a book with “girl” in the title, I found this very interesting!

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

It was interesting the more I looked into it as to how many “Girl” titles there really were in adult fiction. You are part of a big trend, for sure. Best wishes for continued success with both books!

LikeLike