August 30, 2025 was the 70th anniversary of the vicious murder of a 14-year-old Black boy named Emmett Till. In 1955, Emmett Till from Chicago was visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, when he made an unforgivable mistake in the south—he whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant. Three days later, the woman’s husband, brother-in-law and others took Emmett from his bed, tortured and then killed him, dumping his body in the Tallahatchie River. Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, put her son’s mutilated and bloated body on public display in her Chicago church. Some 50,000 people viewed Emmett’s body. A murder trial quickly followed, but the defendants, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, were found not guilty.

The murder and the trial horrified the nation and the world. Till’s death was a spark that helped mobilize the civil rights movement. (American Experience) Three months later, Rosa Parks said she thought of Emmett when she refused to give up her seat on the bus, spurring the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The late Rep. John Lewis linked the racial injustice he witnessed as a youth, with the violence that led to the recent Black Lives Matter movement. “Emmett Till was my George Floyd,” Lewis stated in a posthumous op-ed in the New York Times. “He was my Rayshard Brooks, Sandra Bland and Breonna Taylor.” Lewis realized Emmett could easily have been him. (Emmett Till my George Floyd says John Lewis)

Following is a summary of the events leading up to Emmett’s killing, the kidnapping/murder, the trial, subsequent events surrounding the incident and its impact on family members. Sources include books, articles, filmed interviews, websites, podcasts, trial transcripts, and White House and FBI letters and reports. Whenever possible, I have cited the source of my findings. I gave deference to first-person accounts of family members and trial transcripts if any accounts/information differed. It is my hope that by educating readers with the facts about this murder and its impact on the nation, we can all work to prevent hate crimes like these from ever happening again.

Part 1: The Beginning – Before the Murder

Saturday, August 20, 1955

Although Mamie Till-Mobley agreed to let Emmett visit relatives in the south, she had her reservations. Did she make it clear enough to him in her warnings that things were different down there. That he had to watch what he said and how he acted, always say “No sir. No ma’am.” Step off the curb if a white woman approaches. Don’t look her in the eye. Wait until she passes by, then get back on the sidewalk, keep going, don’t look back. If you have to humble yourself, then just do it. Get on your knees, if you have to.” (Death of Innocence by Mamie Till-Mobley/Christopher Benson, page 101) She would have years to contemplate.

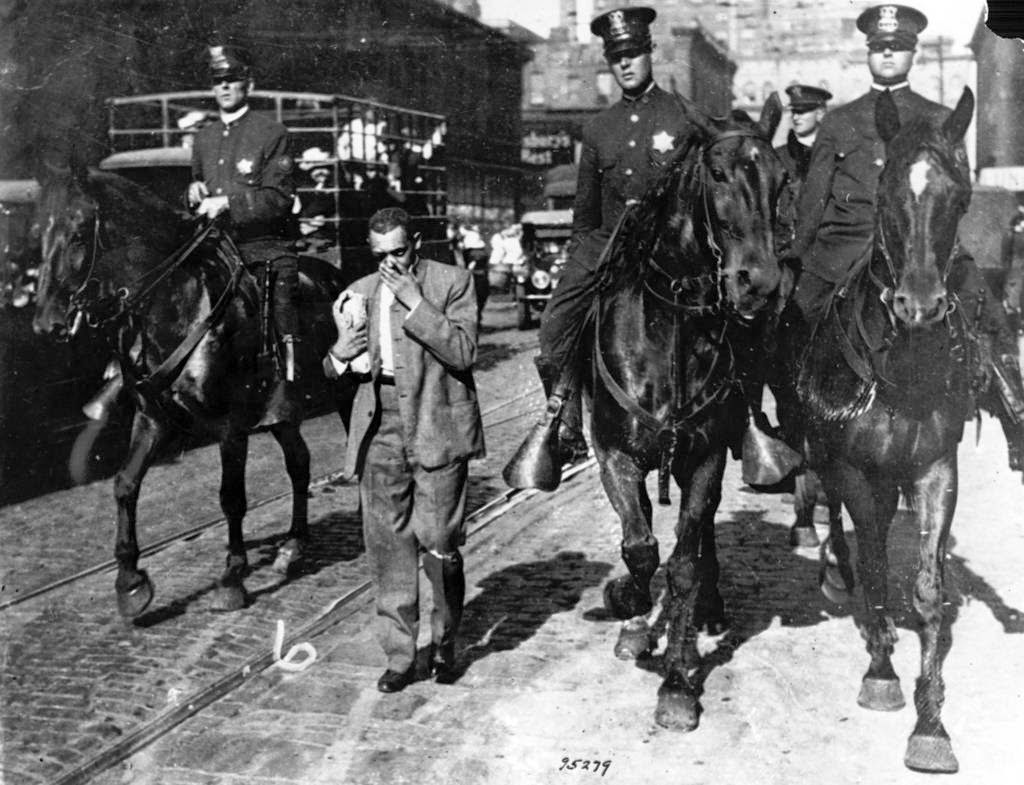

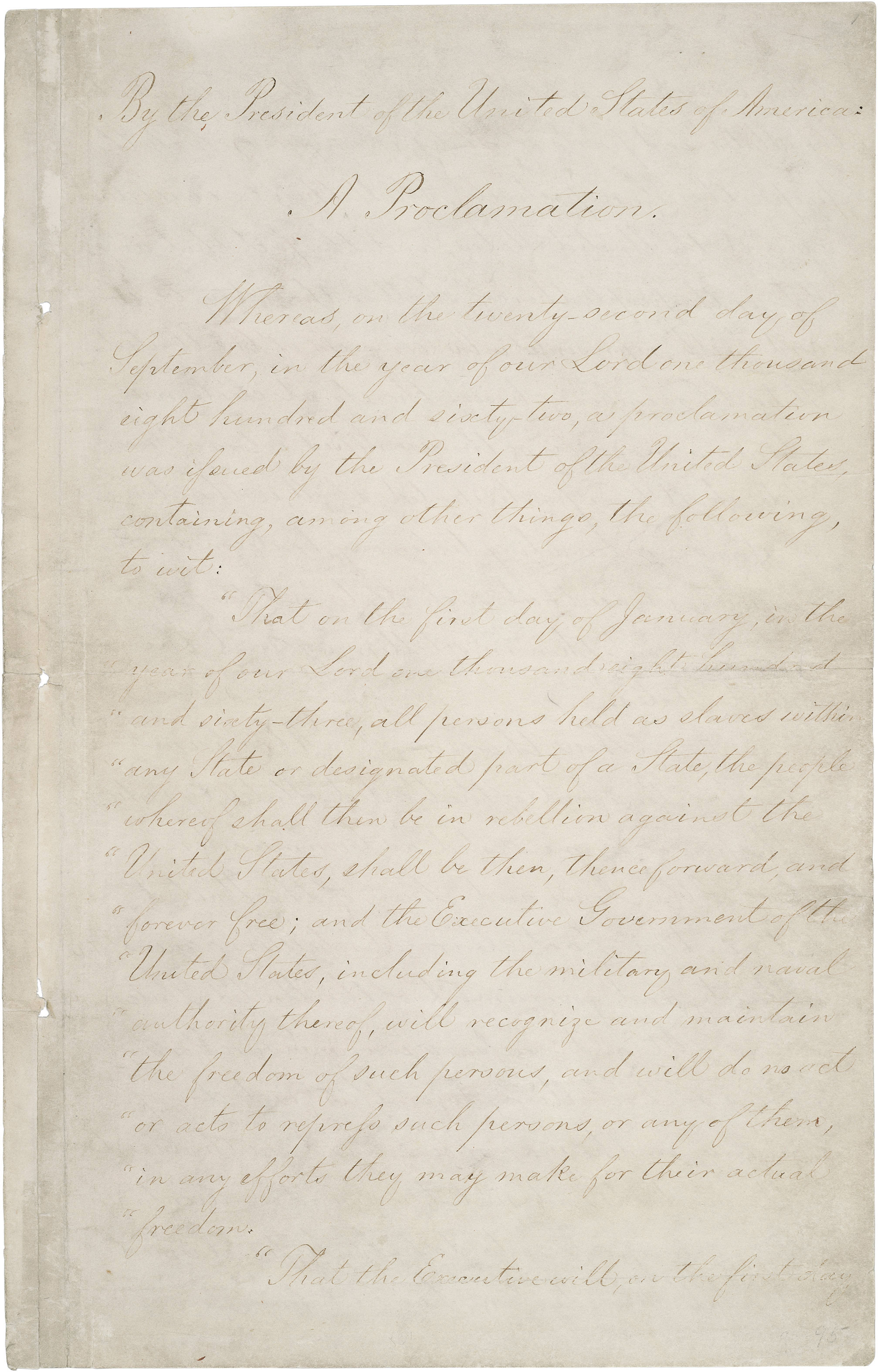

Mamie and her family were aware of the violent reactions to “social transgressions” by Blacks. She had been born in the south, but her family had brought her to Chicago when she was only two years old, though they continued to visit family back home. Jim Crow laws, put in place after Reconstruction following the Civil War, had been designed to “keep Blacks in their place” and make it nearly impossible for Blacks to register to vote and, therefore, serve on juries. This animosity was exacerbated by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, which overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v Ferguson (1896) that had allowed racial segregation in public facilities. (Britannica biography Emmett-Till) Public facilities, including schools, were now to be racially integrated. This federal interference angered those in the south.

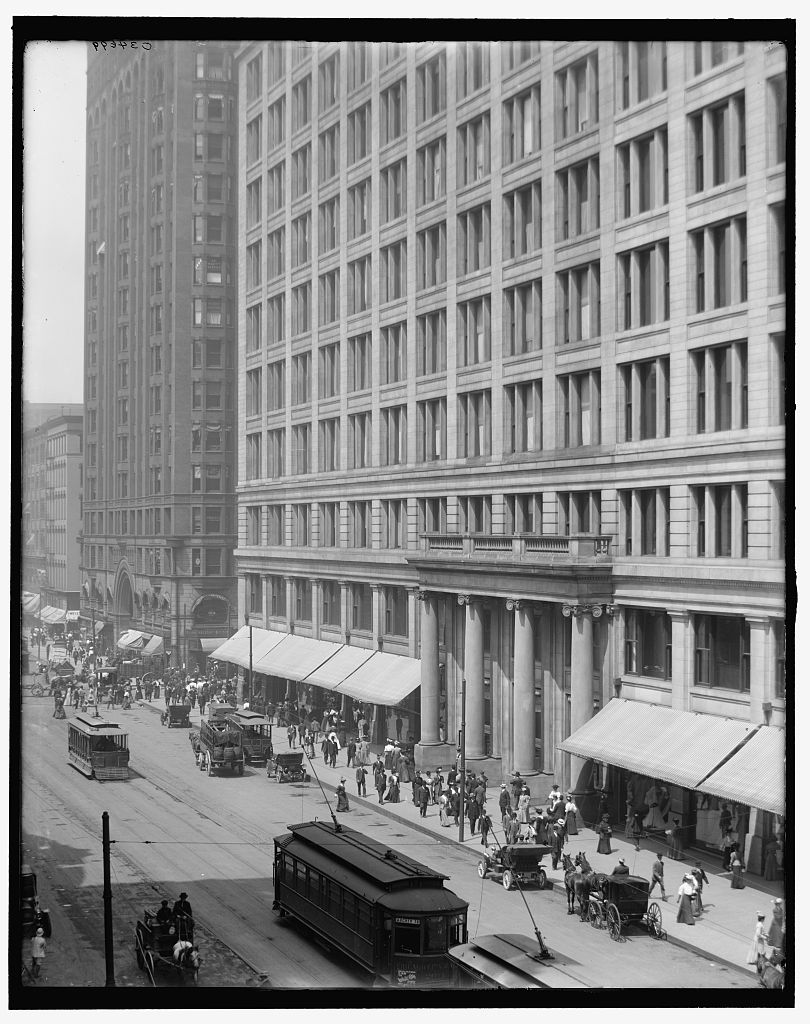

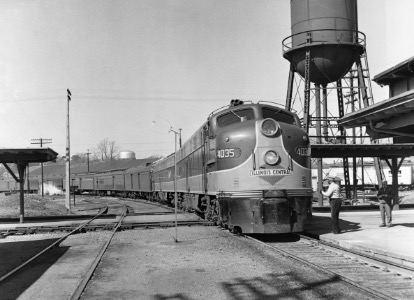

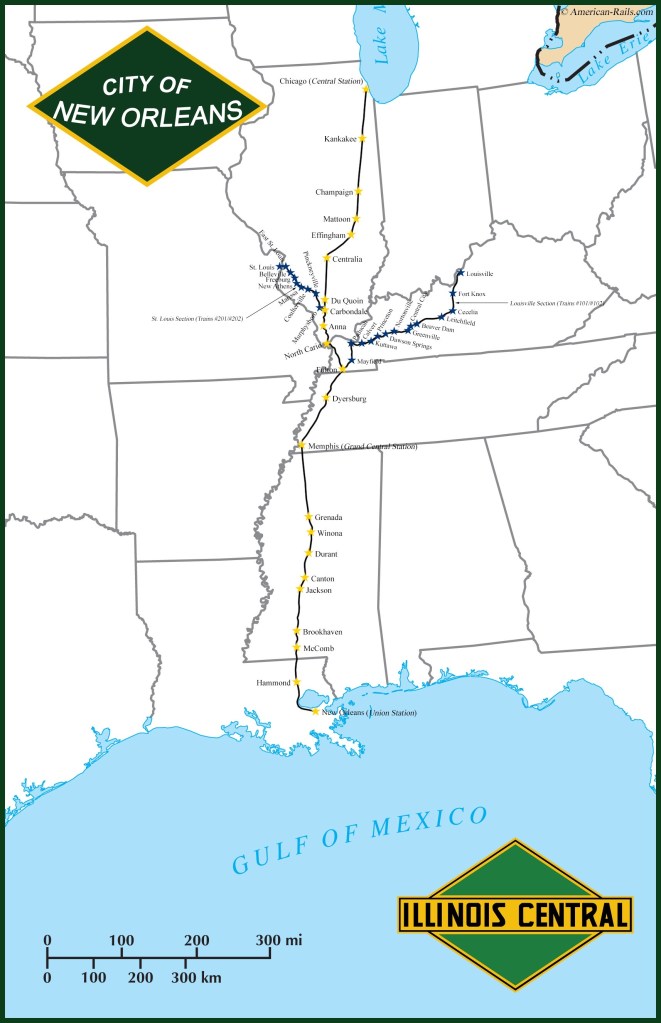

Emmett, who had just turned fourteen years old, was traveling with his great uncle, Moses Wright, who was visiting Chicago for a funeral. Also with them was Emmett’s cousin and best friend Wheeler Parker Jr., aged sixteen. Wheeler was Moses’ grandson. They were passengers on the City of New Orleans—a train line that crossed through northern states, then through southern states all the way down to New Orleans. They met Moses at the Englewood Station at Sixty-third and Woodlawn in Chicago, leaving at 8:01 am. (Death of Innocence, page 104)

Source: http://www.american-rails.com/orleans.html

Mamie packed her son food to take with. Emmett’s lunch box contained his favorite dark meat fried chicken, cake, some treats Emmett had bought himself and a drink—all neatly packed in a shoe box—the same kind of packed lunch Mamie had herself when traveling south as a child. (Death of Innocence, page 104) The trio started in the regular passenger compartments at the beginning of the trip. But, as was custom and law, once they crossed the Mason Dixon line, they had to move to the colored section—directly behind the engine, spewing its soot and smoke.

At 7:25 that Saturday night, the train arrived in Grenada, Mississippi. Papa Moses and the boys were met by Maurice Wright, the oldest son of Papa Moses and Aunt Lizzie. Maurice was waiting with the family’s 1946 Ford sedan for the thirty-mile drive down marked roads and dusty gravel roads to the Wright house on Dark Fear Road just outside of Money. (Simeon’s Story, page 41; Death of Innocence, page 106)

Moses and Elisabeth Wright lived in a large ranch house in the Mississippi Delta. Moses raised cotton, but worked for himself. His “boss” was a German man named Grover Frederick. By all accounts Frederick treated Moses fairly, leaving Moses with a profit every year that he used to support his family through the winter. The Wrights had two ample vegetable gardens behind their home, as did many Blacks at the time, including those up north. This gave them fresh vegetables through the summer and canned goods through the winter. His boss had wanted to take away the gardens and plant cotton right up to the house, but Moses had pushed back strongly and was allowed to keep his vegetable gardens. (Death of Innocence, pages 108-109) Not all Blacks were that lucky.

The first night was a celebration of Moses’ return and the visit from their Chicago relative. During his visit, Emmett, called “Bobo” by his family, regaled them with stories of Chicago—picnics, swimming and events at Lincoln Park; the animals at Lincoln Park Zoo; and the rides and roller coaster of Riverview Amusement Park. (Innocence, page 112; Simeon, page 43) Emmett showed off his Frankenstein comic book and his father’s silver ring, engraved with Louis Till’s initials. (Innocence, page 112) Simeon admired the ring so much, Emmett let him wear it for a couple of days. (Simeon’s Story, page 42)

Three of Moses’ sons were currently staying at the house: Maurice, Robert and Simeon Wright. (Tragedy on Trial, page 15, from trial transcripts). Emmett slept in one of four bedrooms, sharing a bed with Moses’ son Simeon, while Robert slept in another bed. Curtis Jones (who arrived from Chicago a week later) slept in one of the guest bedrooms, Wheeler Parker and Maurice Wright in another, and Moses and Elizabeth/Lillybeth Wright in the final bedroom. The home had a kitchen, dining room, storage room and three porches—the large front screened-in porch spanning the length of the front, a back porch and a side porch. (Simeon’s Story, page 56)

Sunday, August 21, 1955

Early in the trip, Emmett began to see just how different things were. After they bought fireworks from Mr. Wolf’s store in Money, Emmett unexpectedly lit some in front of the store. His cousin Simeon chastised Emmett, as you couldn’t set off firecrackers within the city limits. Simeon later recounted that Emmett wasn’t trying to be funny—he just didn’t know the rules. (Simeon’s Story, page 42)

Emmett’s dress also distinguished him from his cousins. Bobo wore khaki pants or dress pants, short-sleeved cotton shirts, penny loafers and a “Sunday” hat, while his cousins dressed in nylon shirts, overalls and blue jeans.(Simeon’s Story, pages 42 and 45)

Monday, August 22, 1955

Monday was the start of cotton harvest on the sharecropper farm, and Moses had thirty acres to pick, which meant all hands-on deck. Emmett and Wheeler begged to join them in the fields. Cotton picking was “sun to sun”—with occasional afternoons off. But Emmett was not cut out for the drudging toil of picking. The air was heavy, the sun hot, the heat relentless, with no shade. He dragged his nine-foot sack behind him, but was unable to keep up, not picking his share. (Simeon’s Story, page 44)

That night, he told his Aunt Lizzie/Lizzy that’s “it’s too hot and I can’t stand the heat.” Moses relented—Emmett was excused from working the fields. Unlike his cousins, Emmett was allowed to stay home and help his aunt with the household tasks. (Simeon’s Story, page 45) Emmett often helped his mother, Mamie, who worked full-time at her Social Security Administration job. He swept, mopped, waxed, did laundry and even cooked dinner, though Mamie said it was sometimes hard to swallow down his “pepper” corn, laced with too much black pepper for her taste. (Innocence, pages 61 and 83)

Later that evening, Emmett and his cousins were hanging out with several other boys from near-by plantations, one of whom had a gun. Up drove a 17-year-old Black boy named Fletcher, who threatened to take to gun. Fletcher had a higher standing, as he drove a tractor for the owner of his plantation, and was “mean as a snake.” When the group did not stand up to him, going silent, Emmett later struck out at his cousins. “How can you let someone come on your turf and strut his stuff? You can’t allow anyone to come around and disrespect you like that. We would never tolerate this in Chicago.” (Simeon’s Story, pages 46-47)

But this was not Chicago.

Tuesday, August 23, 1955

Emmet waited for his cousins to return from the fields, so he could continue his antics and his storytelling. Simeon said Emmett might have grown up to be a comedian as he could recite all the routines of all the top ones on television—Red Skelton, Jack Benny, Abbott and Costello, and George Gobel. (Simeon’s Story, page 47)

In an effort to entertain the Chicago boys, Emmett’s cousins “borrowed” some melons from a watermelon patch, throwing them on the ground to crack them open, exposing the sweet center flesh. Later, they headed down to the water, running out the snakes before going in to swim. (Simeon’s Story, pages 48-49) The visit was going well.

Part 2: The Incident at Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market

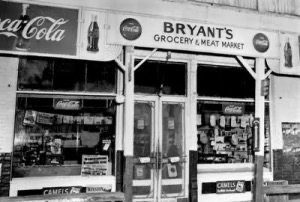

(From Ed Clark; Life Pictures/Shutterstock.)

Wednesday, August 24, 1955

After his cousins returned from working in the fields, Emmett, Simeon, Wheeler, Maurice, and two neighbors, loaded into the old Ford to travel for some candy and perhaps a cold RC cola to cool down. (Simeon’s Story, page 49) [In his book, The Barn, Wright Thompson identified the two neighbors as Ruthie Mae Crawford and Roosevelt Crawford, but Simeon Wright insisted more than fifty years later that Ruthie wasn’t there. (The Barn, page 239) Timothy Tyson, in his book, The Blood of Emmett Till, stated that six boys and one girl made the trip: Emmett, Maurice, Wheeler, Simeon, and neighbors Thelton “Pete” Parker, Ruthie Mae Crawford, eighteen, and her uncle Roosevelt Crawford, fifteen. (The Blood of Emmett Till, page 51)] Maurice, the oldest of the Wright brethren at sixteen years old, took the wheel as the sun was just disappearing over the horizon. There were no adults along as Maurice had dropped off Moses and Elizabeth at church. Per Moses’ directive, the teens were only supposed to go to the little country store out in East Money on the plantation, as Maurice had no license. (The Barn, pages 239-240; The Blood of Emmett Till, page 51) Instead, they travelled further to Money, Mississippi, to Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market. (Simeon’s Story, page 49) It would turn out to be a horrible mistake.

Although accounts differ as to what Emmett said or did that evening, personal accounts by both Simeon and Maurice indicate nothing inappropriate happened in the store. Emmett followed Wheeler into the store. When Wheeler returned to the porch to eat his ice cream cone, Maurice noticed Emmet had not yet come out and sent Simeon in to get him, and to make sure Emmett was watching his manners. Nothing seemed amiss. Emmett had his two cents’ worth of bubble gum (American Experience: Getting Away with Murder) and Bryant did not seem flustered in any way. Simeon and Emmett left the store together, and the sharecroppers on the porch continued their checker games as the boys watched. (Interview of Wheeler Parker with Dave Tell and Theon Hill, May 11, 2023; the Chicago Crusader) Emmett had been alone in the store with Carolyn Bryant for less than a minute. (Simeon’s Story, page 50)

Some speculate that Emmett may have brushed Carolyn’s hand when giving her his money instead of putting the money on the counter, a social code that a black man was never to touch a white woman. Did Emmett flirt with her? Maybe? Maurice Wright said Emmett told Carolyn Bryant “Goodbye” as he left the store, but did not say “ma’am.”(The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi, Wright Thompson, page 243) Moses said in the days before the incident, Emmett has delighted in not adopting that little soul-crushing bit of deference. (The Barn, page 243.) Did Emmett grab her by the waist and propose sex with her, as Carolyn Bryant later testified? The latter seems highly unlikely. As Simeon noted in his book, a counter separated the customers from the store clerk; Bobo would have had to jump over it to get to Mrs. Bryant. (Simeon’s Story, pages 50-51) The width of the big glass cases (serving as the counter) was too great for people to, say, hug. (The Barn, page 242) And further, Emmett had a pronounced lisp, a result of having polio at age six, (Innocence, pages 37-40) so likely could not have even gotten those words out. If Carolyn Bryant had called out, if voices had been raised, the Black checker players on the porch would have heard them—the screens were open, with sound floating freely from inside to out, and vice versa. (The Barn, page 241) But for that single minute, no one was in the store except Carolyn and Emmett. Only the two of them knew what truly transpired.

Then, for reasons that are unclear, Carolyn Bryant exited the store. Perhaps, as Parker speculated, she was curious about all the talking and laughing on the porch. (Wheeler Parker oral history interview by Joseph Mosnier, Library of Congress) Perhaps, she went to get something out of her sister-in-law’s car, parked alongside the store. (The Barn, page 243) Some think she looked mad and was going to get her gun. In her memoir, Carolyn said she had looked for the gun inside the store, and realizing it was in the car, had gone out to get it. (The Barn, page 252) Others believe the whistle is what prompted her to want to get the gun. (The Barn, page 243)

The Whistle

What is not denied is that as Carolyn Bryant headed toward the vehicle, Emmett whistled—a long, shrill “whee wheeeee!” that Simeon described as a wolf whistle. (Simeon’s Story, page 51, NPR Simeon Death and multiple other sources) The whistle broke the peaceful night air. Emmett’s cousins grew stiff, looking at each other in fear and panic, knowing that Emmett had broken a social taboo about conduct between Blacks and whites in the South. (Simeon’s Story, page 51) Carolyn now hurried her pace to her car, and kids at the store said she was going for a gun. (American Experience emmett-biography) The checker players scrambled off the porch. Sensing danger, the cousins gathered Emmett and raced toward the Wright’s car. It was only then that Emmett, the jokester, realized he had done something very wrong. (Simeon’s Story, page 51)

As they tumbled in, Maurice hesitated. Simeon described the scramble to pick up a lit cigarette that had fallen on the floor. (Simeon’s Story, page 51; The Barn, page 244) Once found, the boys yelled for Maurice to “drive!” and they sped off down the dark road. Soon, they saw headlights and feared for their lives. “They’re after us!” Chicago Sun-Times Wheeler Parker Eyewitness) Maurice knew he couldn’t outrun another car in the old Ford, so pulled over and the boys jumped out, racing into the cotton fields, unopened bolls scratching their legs, causing Wheeler and Bobo to fall to the ground. Simeon, afraid he couldn’t catch up or that he might get lost, stayed in the car, but slipped down in the seat out of view. (Simeon’s Story, page 52) But the car passed by—just a neighbor going home. (Innocence, pages 122-123) No one was after them, yet.

Emmett begged his cousins not to tell his great-uncle, for fear he’d be sent back, ending his vacation early. They agreed. They returned home without mentioning the incident to Moses. They kept Emmett’s secret. (Simeon’s Story, page 53)

Thursday, August 25, 1955

At daybreak, Emmett’s cousins headed for the cotton fields. In the evening, a neighbor girl, Rutha/Ruthie Mae Crawford, told Moses and Elisabeth what happened, and warned that these white men would not take this lightly. Trouble was brewing. “You’re going to hear more about this. We know these people.” (Simeon Oral History, Library of Congress.) She suggested Emmett should leave for Chicago immediately.

Friday, August 26, 1955

The day passed without incident. It had been several days now since the wolf whistle at the Bryant grocery store. The boys felt that the danger had died down.

Saturday, August 27, 1955

The young folk were excited for a big night in Greenwood—a big city in comparison to the rural life they lead, with juke joints, movie theaters, ice cream shops and vendors selling hot tamales, fried fish and foot-long hotdogs. Maurice, Bobo, Wheeler and neighbor Roosevelt Crawford walked the main strip, Johnson Street, looking into nightclubs and watching people dance through the smoke. (The Barn, page 247) Simeon, garnering a ride from Roosevelt’s older brother John Crawford, watched a western movie. Their final stop was a house party on the Four Fifths Planation northwest of Greenwood, a “juke joint.” They arrived home after midnight. (Simeon’s Story, pages 54-55; The Barn, pages 247-248) [In the trial transcripts, Moses stated he went with the youngsters, (Tragedy on Trial, page 15) but neither Simeon nor Wheeler ever mention that Moses accompanied them.] Curtis Jones, Willie Mae’s son, another of Emmett’s cousins, had arrived at Moses’ home from Chicago during their outing. (Innocence, page 115) Robert had stayed home to listen to his favorite radio program, Gunsmoke. (Simeon’s Story, page 54)

Part 3: When Men Came Knocking

Sunday, August 28, 1955

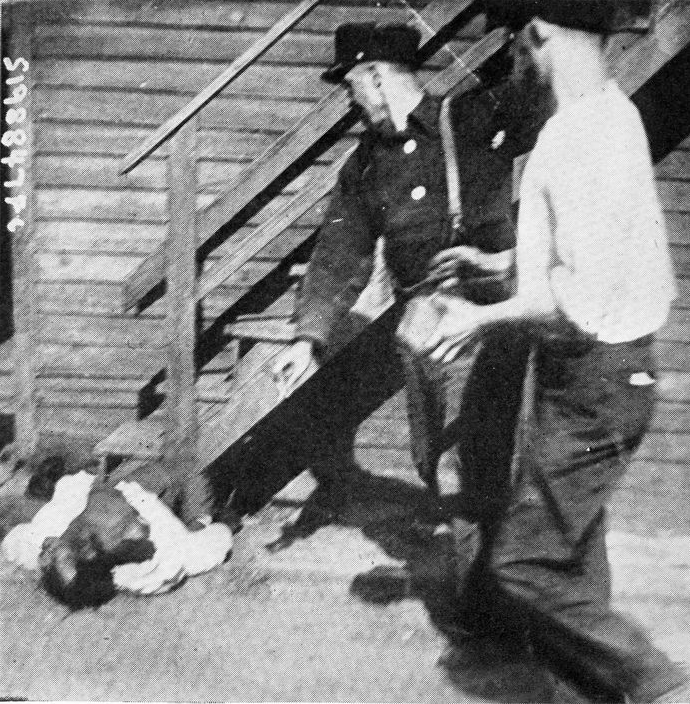

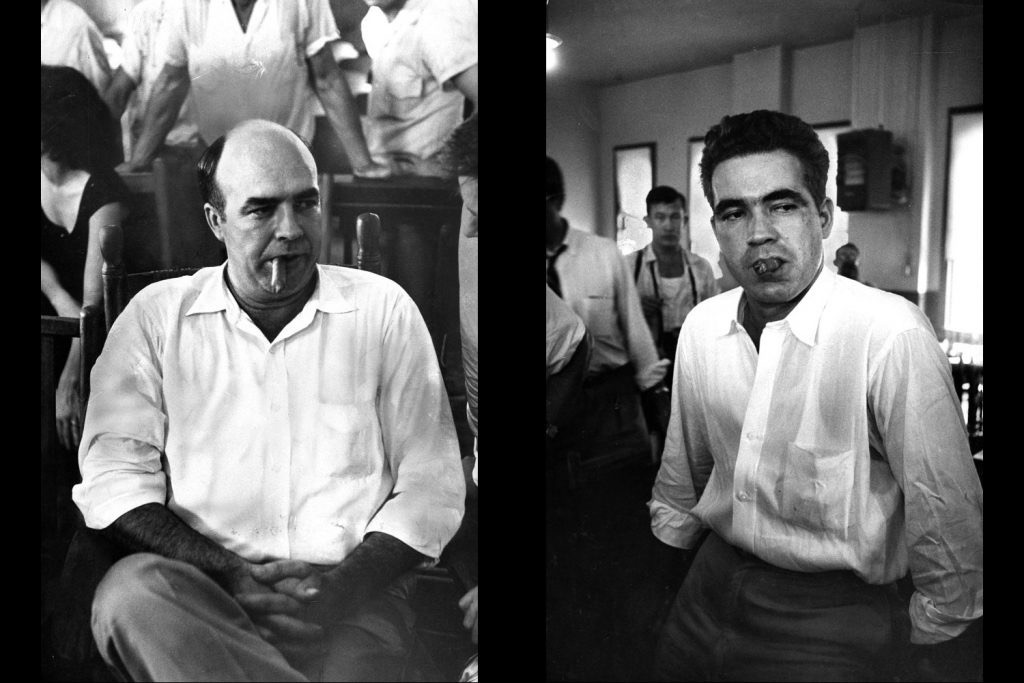

Early Sunday morning at about 2:00-2:30 am, three men appeared on Moses’ porch—two white and one black. The first white man was Roy Bryant. The other white man was tall and large, brandishing a flashlight in his left hand and his Ithaca .45 in his right. (The Barn, page 258) That man was J.W. Milam.

(The rest of the text in this section is taken directly from the trial transcripts of Moses’ testimony, from Tragedy on Trial, pages 15-25, unless otherwise noted)

Bryant had awakened Moses by calling his nickname, “Preacher!”

“Who is it?” Moses asked.

“This is Mr. Bryant.”

“Yes, sir,” Wright said and opened the door to find Milam in the doorway, Bryant standing somewhat behind him, and the third man by the screen door. [The third man Moses surmised was Black because he stayed in the background outside with his head down to hide himself, acting like a Black man. (The Barn, page 258) Many believe that black man was Johnny Washington, who hung around the Bryant store. Moses Wright believed Washington told Milam and Bryant where Emmett was staying and accompanied them to Wright’s home. Nobody could ever prove it. (The Barn, page 255)]

“You got two boys from Chicago?” Milam asked.

“Yes sir,” Moses replied, thinking of Wheeler and Emmett.

“I want that boy who done the talking down at Money,” Milam said.

Moses led Milam and Bryant through the house—first past the bedroom of Wheeler and Maurice, Milam shining the flashlight across their faces, past the second bedroom where Curtis still slept soundly without ever waking (The Barn, page 260, quoting Simeon Wright), to the final bedroom, where Emmett and Simeon lay sleeping.

Moses shook Emmett awake. Milam spoke in the dark.

“Are you the one who did the smart talk up at Money?”

“Yeah,” Emmett said.

“Don’t you ‘yeah’ me. I’ll blow your head off. You say ‘Yes, sir.’ ” (The Barn, pages 260-261)

Milam instructed Emmett to get up. Emmett sat on the side of the bed and dressed, insisting they wait while he put on his sox before putting on his shoes. Once Emmett rose, the three of them started out. The Wrights begged them not to take Emmett. Moses suggested that they just whip Emmett, that Emmett didn’t know what he’d done since he wasn’t from the south. Elizabeth approached the men, pleading that “we will pay you whatever you want to charge if you will just release him. We’ll pay for whatever he might have done if you just let him go.”

The men did not reply to Elizabeth’s offer. Milam instructed her to “get back in bed—I mean I want to hear the springs squeak.”

Milam then asked Moses, “Do you know anyone here?” Moses responded that he did not.

“How old are you?”

“Sixty-four.”

“Well, if you know any of us here tonight, then you will never live to be sixty-five.”

They took Emmett out to their car as Moses stood by the screen door at the front of house. Moses heard the men ask if this was the boy, and someone said “Yes,” in a voice lighter than a man’s.

Moses believed until his dying day that the voice in the truck was Carolyn Bryant’s. (The Barn, pgs 262-263)

After the men left with Emmett, Elizabeth Wright ran next store to their white neighbors and begged to use the Chamblee’s’ phone. Mrs. Chamblee wanted to help, but her husband, “the straw boss,” said no. Robert, Maurice and Curtis still slept soundly. Wheeler and Simeon stayed frozen in fear in the darkness. Wheeler decided if the men returned, he would run, even putting on his shoes in preparation.

“It was horrible,” Wheeler later said. “It seemed like day would never come.” (The Barn, page 261.)

Anxiously, the family waited for first light. Moses thought they would just whip him and bring him back. In fact, Bryant and Milam said if Emmett wasn’t the one, they’d bring him back and put him to bed.

But that’s not what happened. They never saw Emmett alive again.

Part 4: The Horrible News Reaches Mamie

Early Morning Sunday, August 28, 1955

In the hours after the kidnapping, Moses Wright got a friend to drive him to the Bryant grocery store. Moses knocked, and then knocked again. Though he felt someone was there, no one came to answer the door. It was then that he knew. Emmett was dead. They began to search under bridges and on the banks of the rivers and bayous. (The Barn, page 266)

Meanwhile, Curtis Jones went to the home of Grover Frederick, the owner of Moses’ land. He called his mother, Willie Mae Wright Parker, in Chicago to tell her that Emmett had been taken and was still missing. Willie Mae had the heart-wrenching task of telling Mamie. (The Barn, page 266)

When the phone rang at about 9:30 am, Mamie picked up the receiver. “Hello,” she said. But there was silence. She said “hello” again.

“Finally, the voice came through. “This is Willie Mae. I don’t know how to tell you. Bo.”

“Bo, what?” Mamie sat up, her heart racing. “Willie Mae, what about Bo?”

“Some men came and got him last night.” (Innocence, page 114)

Mamie went to her mother’s home. Though her mother, Alma Smith Carthan Spearman, had always been the strong one, Alma crumbled at the news. It was up to Mamie to act. She contacted the newspapers and reporters came out. Mamie and Alma also contacted Rayfield Mooty, a relative of Alma’s husband Henry Spearman, and the head of the Steelworkers Local union and someone with contacts with politicians and civil rights people. Mooty had been touched by Bo, and vowed to do everything he could to help. (Innocence, page 119) Mamie’s friend, Ollie Williams, worked for Inland Steel Container Company, and contacted her supervisor who was the head of industrial relations. Inland Steel had offices in the south—New Orleans and Memphis. (Innocence pages 119-120.)

Unable to reach Moses, they called Alma’s brother, Crosby Smith, who still lived in Mississippi. Everyone else was safe. Uncle Crosby was going to the sheriff with Papa Moses. (Innocence, page 120) Moses Wright identified Roy Brant and J.W. Milam as the two men who had kidnapped Emmett from his home. The authorities in Mississippi were now on notice.

Part 5: Mamie Expands Pressure to Find Emmett Through the Press, Politicians and the NAACP

Monday, August 29, 1955

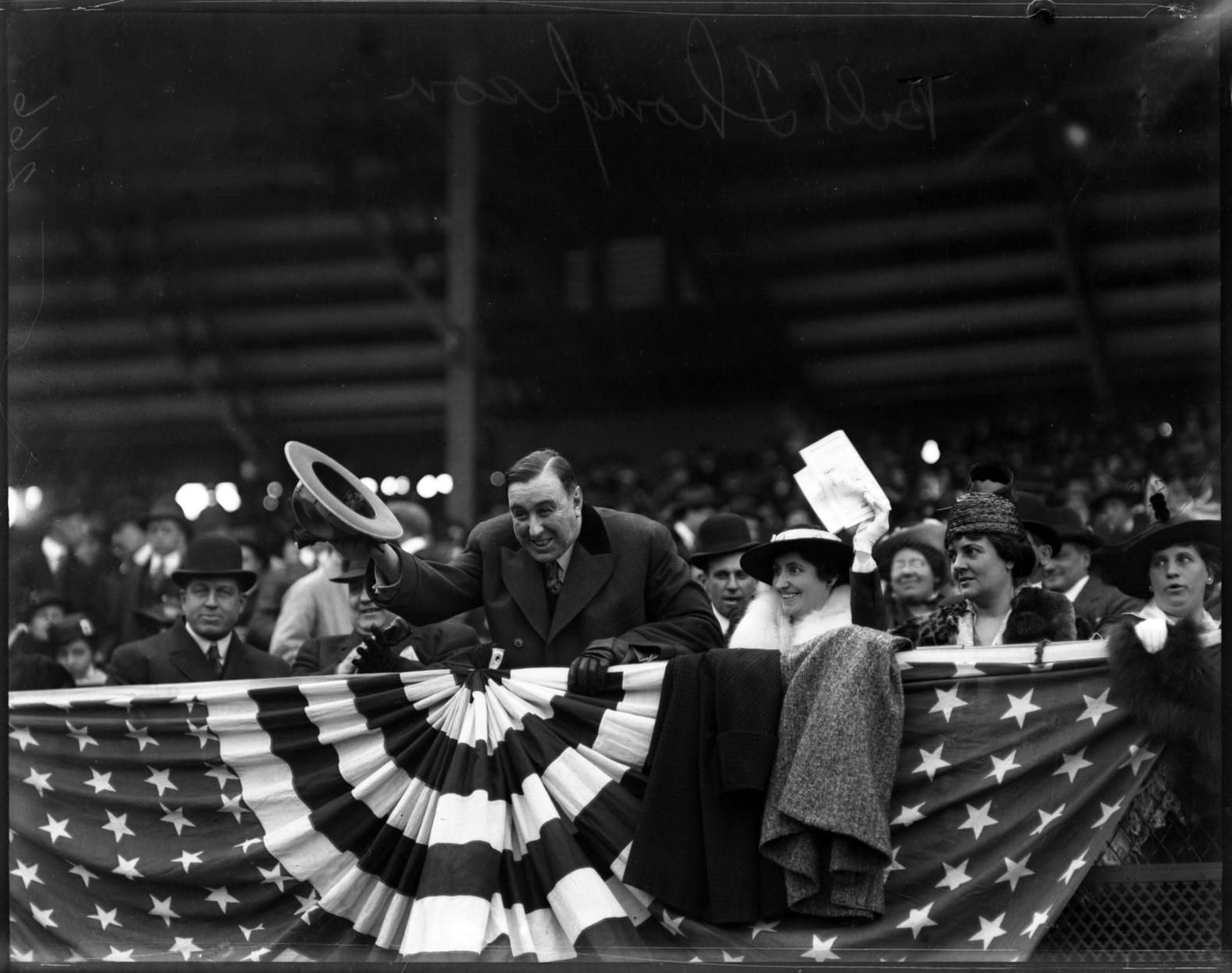

Rayfield arranged for Mamie to meet with the Chicago branch of the NAACP, connecting with William Henry Huff, the counsel for the Chicago branch and chairman of the branch’s Legal Redress Committee. Rayfield Mooty and William Huff exerted pressure to make the story of Emmett into news. The story was being carried in Chicago newspapers. Local and state officials began pressing Mississippi authorities to find Emmett. Even the Chicago mayor, Richard J. Daley, was involved, as was the Illinois Governor, William Stratton, and William Dawson, a powerful South side congressman. Ollie’s boss at Inland Steel contacted the president of the company who told his Southern offices to put their planes on the lookout as they flew over the area in Mississippi where Emmett had been taken. (Innocence, page 120) Emmett’s disappearance was gaining attention.

Though, like any mother would, Mamie wanted to travel immediately to Mississippi, Uncle Crosby convinced her to stay in Chicago. He would take care of things down south.

Wheeler Parker had been smuggled out of town to Duck Hill by his uncles Elbert Parker, Sr. and William Parker Sr., who—at great risk to their own safety—got Wheeler on a train back to Chicago. (Wheeler’s Uncles Help Him Escape) When Wheeler arrived at Alma’s home in Chicago, Mamie stopped him on his way across the room to her. Wheeler and Bo had been best friends. They loved each other. Mamie found the grace to send Wheeler to Willie Mae. “Go hug your mother.” (Innocence page 121)

Part 6: Kidnapping Charges are Brought Against Bryant and Milam

Tuesday, August 30, 1955

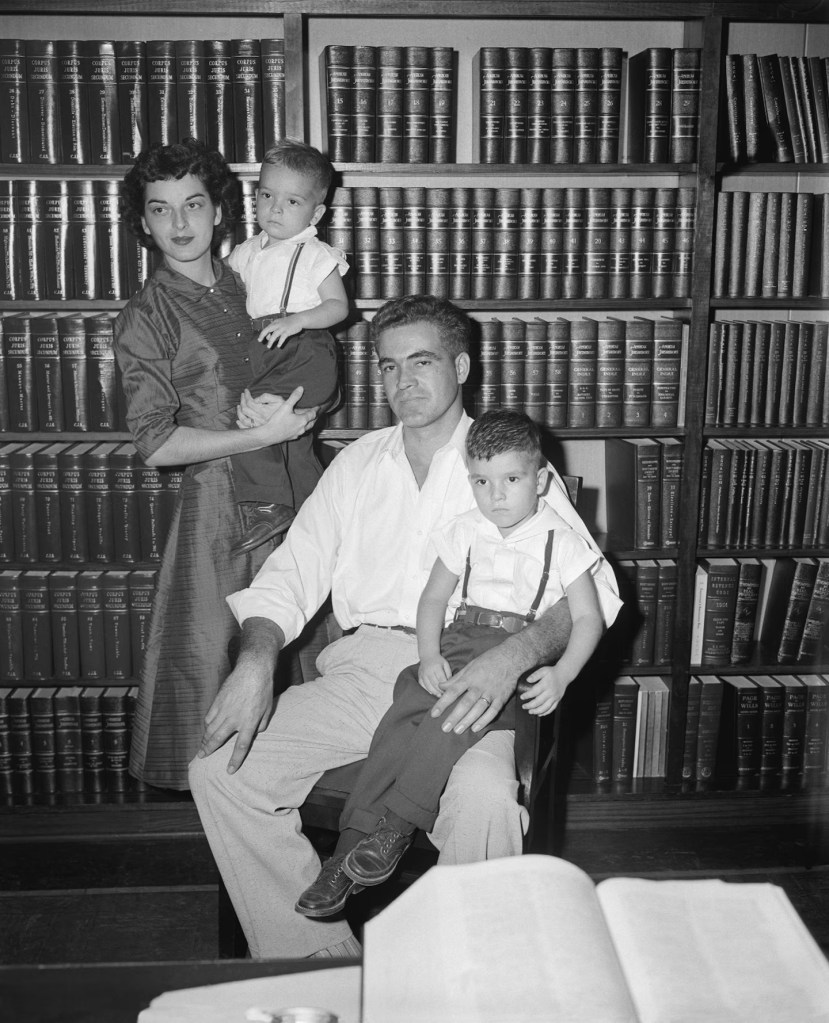

George Smith, the Sheriff of Leflore County, Mississippi, announced the arrest of two white men on kidnapping charges: Roy Bryant and J.W. “Big” Milam. They were held in jail without bond. (Emmett Till Legacy Foundation; The Barn, page 280) They admitted to taking Emmett, but said they had let him go. (Innocence page 120) This gave Mamie momentary hope that Emmett was still alive.

In Chicago, they waited. Attorney Huff gave her an update and showed Mamie telegrams he had sent to Illinois Governor William Grant Stratton and Mississippi Governor Hugh White. Mamie left her mother’s house to get money to send to Uncle Crosby. Upon her return, her mother said that they’d been informed that Bo might be on his way home. But after calling the police, Mamie realized they had been victims of a hoax. Bo had not been found. It was only the first phase in discovering he full measure of human cruelty. (Innocence page 126)

Part 7: Emmett’s Bludgeoned Body is Discovered in the Tallahatchie River

Wednesday, August 31, 1955

On the morning of August 31, young Robert Hodges was checking his trotlines in the Tallahatchie River when he noticed something odd: two feet projecting out of the water. Hodges rushed home to tell his father, who called his landlord, B.L. Mims, who relayed the information to the police. The Tallahatchie County sheriff’s office dispatched people to the scene. The first to arrive was Deputy Garland Melton. Together with Mims, Melton towed the body back to shore. (The Barn, page 276) The men removed the 74-lb cotton gin fan, which was attached to the body by barbed wire wrapped around Emmett’s neck—the weight meant to keep the body submerged, to keep the murder a secret. At some point, Tallahatchie Sheriff Strider arrived, as did Leflore County Deputy Sheriff John Ed Cothran.

Sheriff H.C. Strider, took control, though it was not clear he had jurisdiction, as the site of the actual murder had not been confirmed. Moses Wright was called to identify it. The naked body was bloated, and badly beaten and disfigured, but there was one recognizable item—the ring of Louis Till. It was still on Emmett’s hand.

Strider then ordered the immediate burial of Till and had the coffin sealed under penalty of law to prevent its opening or transportation. The body was released to the Tutwiler Funeral Home, operated by the town Mayor Chick Nelson. (Emmett Till Memory Project – Tutwiler)

In Chicago, the news came from a reporter. He called Alma’s house, but didn’t want to speak to Mamie. He requested the phone number of someone else he could call. Mamie knew. When her friend Ollie Williams came over and stood in the doorway, Mamie had confirmation. Ollie’s look said it all. Emmett was dead. They’d found his body in the Tallahatchie River. (Innocence, page 126)

Mamie hugged her mother, her rock, the one who always took charge, but her mother was depleted. And then, as if in a transfer of strength, Mamie realized that the only one she could count on was herself. (Innocence, page 127)

Part 8: A Mother’s Love and Courage: Mamie Demands Emmett be Returned to Chicago

When word came that Emmett’s body was being buried that day, in Mississippi, Mamie did something very courageous. She demanded the body be brought back to Chicago. They contacted A.A. Rayner, one of the most respected Black Funeral directors in Chicago. Together with Uncle Crosby, Rayner made arrangements for Emmett’s body to be placed on the train Thursday night. Crosby would accompany the body for Emmett’s return—just two short weeks after Emmett had ridden that same train south so full of joy and anticipation at seeing his cousins. (Innocence page 130)

“They were not going to bury my boy in Mississippi. He would be coming home. Finally, Bo would be coming home.” Mamie (Innocence, page 130)

Friday, September 2, 1955

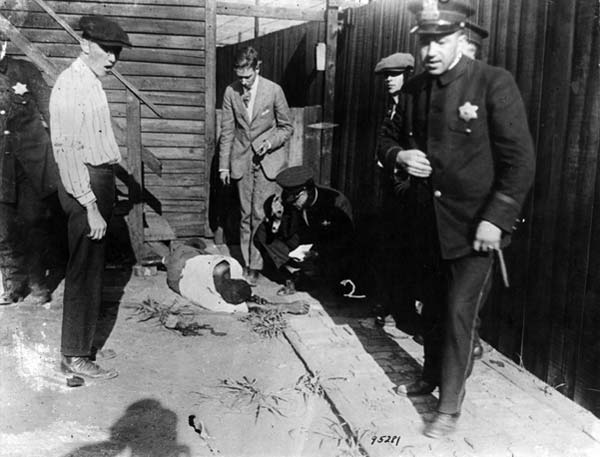

Chicago History Museum, STM-092678138, Dave Mann/Chicago Sun-Times

A crowd had gathered at the Twelfth Street station. Mamie was accompanied by her husband, her father, Rayfield Mooty, a few cousins, and Bishop Louis Henry Ford and Bishop Isaiah Roberts. (Innocence, page 131) After Emmett was transferred to the A.A. Rayner Funeral Home in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago, Mamie insisted the box be opened.

“Oh, Mrs. Bradley,” Mr. Rayner said, “we can’t open that box.”

Rayner explained that the seal of Mississippi was on the box, and that promises had been made to keep it sealed, that it was how they’d gotten Bo’s body out of Mississippi, that all of them had signed papers promising to keep it shut—Rayner, the undertaker and Mamie’s family. But Mamie would not relent. She had to know. She had to see for herself what they had done to her son. (Innocence, page131) When Rayner continued to resist, Mamie said she’d take a hammer and open it herself.

“You see, I didn’t sign any papers and I dare them to sue me. Let them come to Chicago and sue me.” She thought, what judge would deny her, find her guilty of viewing the body of her baby. (Innocence page 132) Finally, Rayner relented, but he wanted time to prepare the body. Mamie waited.

The funeral home laid the body out on a table. Her husband, Gennie “Gene” Mobley, held one of her arms, her father the other. Mamie settled herself, despite her terror. If she hesitated, she might miss this chance. She couldn’t yet look at Emmett’s face, so started with his feet, then his ankles, shaped thinner than her own. She moved to his legs, marveling at how strong they’d become, despite his bout with polio at age six. She paused at his knees, round and rather flat, just like hers. She moved further up to his private area, relieved that everything was intact. There’d been so many rumors. The skin was lose, but the body so far has not shown scars—until she got to his face. His tongue rested on his chin, An eyeball hung down on his right check. She looked at the eye, confirming its color—a light hazel brown that everyone thought was so pretty. She looked at his teeth, then at the bridge of his nose between his eyebrows, which had been chopped, as if with a meat cleaver. Next, she went to his ears. The distinctive little twist on the lobe had been cut off. She saw that someone or something had cut through the top of his head from ear to ear. The back of his head was loose from the front, and she could see clear through the bullet hole from one side of his head to the other. (Innocence, pages 134-136)

She had to stop. She didn’t need to compare the body with the photos of Emmett she’d brought. Yes, it was her son. Yes, it was Bo.

Part 9: Mamie Bears Witness

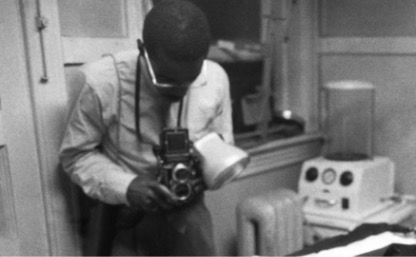

Mamie Till-Mobley invited David Jackson to photograph Emmett’s body and provided images to national and international press outlets

Then Mamie did something remarkable. She invited Jet photographer David Jackson to take photos of Emmett’s body on the cart. When Rayner gently asked if Mamie wanted his team to work on the body, to make it more presentable, Mamie declined. “Let the world see what I’ve seen.” (The Barn, page 280) In the now infamous images, Emmett’s bloated, brutalized face is shown up close, with Mamie stoically standing in the background. (Time Till Civil Rights Photos)

The photos appeared first in Jet magazine, and then in the Chicago Defender, publications with Black-based content and readership. No white papers carried them; yet, the photos were out there—testimony to the raging violence inflicted upon Emmett’s body.

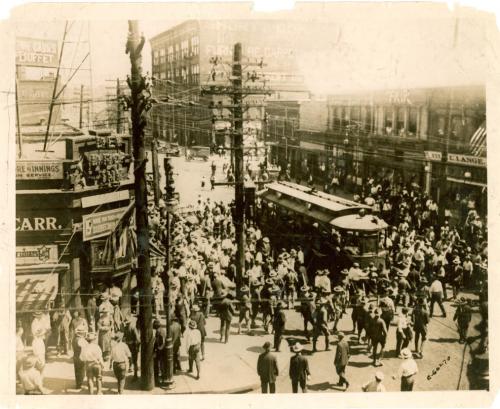

Part 10: Let the World See What I’ve Seen: Tens of Thousands View Emmett’s Body

The next remarkable thing Mamie Till-Mobley did was to publicly display Emmett’s body. She made the decision to keep her son’s body as it was, without further “work,” and have a public, open-casket funeral “so everyone can see what they did to my boy.” Emmett’s body lay in a casket with glass over the top to help prevent the awful smell from leaching out. It didn’t work. Thousands of people lined up outside the A.A. Rayner Funeral Home through that Friday night to pay their respects. Tens thousands more spilled into the streets in front of the Robert’s Temple Church of God in Christ, Mamie and Alma’s church, and waited hours to view the body, while the eulogy was broadcast over a public-address system. (The Defender: How the Legendary Black Newspaper Changed America by Ethan Michaeli, page 325) Women fainted. Even strong men wept. And the young men who viewed Emmett’s bloated body could not help but think that it could have been them. So many people came that the viewing was extended an additional day.

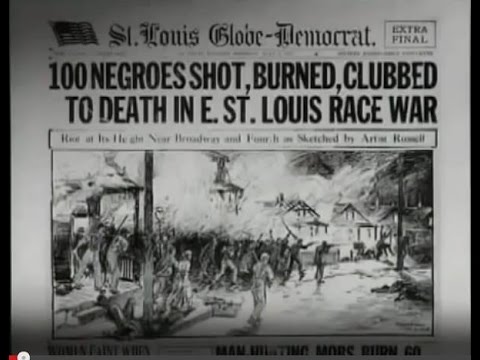

Part 11: The Southern Response

Although the images of Emmett’s body and the crowds outside the Robert’s Temple Church of Christ garnered national—and even worldwide—condemnation and sympathy, not everyone was supportive of Mamie’s bold actions. Some Mississippi residents felt that the entire state was being dragged through the mud because of the actions of a few “peckerheads.” They resented Mamie’s boldness and the cutting comments of the NAACP.

When Roy Wilkins, Executive Secretary of the NAACP, described the Till killing as a “lynching” and commented that “the state of Mississippi has decided to maintain white supremacy by murdering children,” many Mississippians were deeply offended and angered. According to historian Hugh Whitaker, the strident remarks of Wilkins and other northern opponents of segregation caused the local power structure to dig in and throw support to Bryant and Milam, two men they otherwise might have been happy to see put away. (Famous Trials Till Murder citing Hugh Stephen Whitaker’s thesis, “A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Emmett Till Case,” published in August, 1963, Florida State University.)

Mississippi newspapers and public officials who had initially been outraged at the murders, now began to take a slightly different tact. They attacked northern interference and accusations. In an outrageous turn of events, the very sheriff in charge of investigating the case, Tallahatchie Sheriff Clarence Strider, stunned those attending a press conference when he voiced what many in the local white community felt:

“We never have any trouble until some of our Southern [expletive]s go up North and the NAACP talks to ‘em and they come back home. If they would keep their nose and mouths out of our business, we would be able to do more when enforcing the laws of Tallahatchie County and Mississippi.”

Further, Sheriff Strider went on to testify for the defense, casting doubt that the body was in fact that of Emmett Till. More about Strider in an upcoming blog.

To Come in Future Blogs:

Strider and the Trial: How It Was Rigged from the Beginning

The Black Press and the Emmett Till Murder

Although the Gibson Girls seemed to fit Charles Dana Gibson’s view of a kinder, gentler New Woman, Gibson’s own wife Irene Langhorn Gibson was anything but demure. Irene, who may have been the first Gibson Girls model, was a known suffragette, the chair of the Eastern Women’s Bureau of the Democratic National Committee (in support of Woodrow Wilson’s reelection in 1916) and a champion of philanthropic causes, such as co-founding Big Sisters, helping troubled girls. A feat she could accomplish with her Virginia fortune and can-do attitude.

Although the Gibson Girls seemed to fit Charles Dana Gibson’s view of a kinder, gentler New Woman, Gibson’s own wife Irene Langhorn Gibson was anything but demure. Irene, who may have been the first Gibson Girls model, was a known suffragette, the chair of the Eastern Women’s Bureau of the Democratic National Committee (in support of Woodrow Wilson’s reelection in 1916) and a champion of philanthropic causes, such as co-founding Big Sisters, helping troubled girls. A feat she could accomplish with her Virginia fortune and can-do attitude. Gibson’s first and favorite model was Evelyn Nesbit. While sources vary on whether she actually ever sat for Gibson, he could easily have found images of Nesbit in the press. She was involved in a love triangle, where her current husband murdered a former lover.

Gibson’s first and favorite model was Evelyn Nesbit. While sources vary on whether she actually ever sat for Gibson, he could easily have found images of Nesbit in the press. She was involved in a love triangle, where her current husband murdered a former lover.

In past “Girl” best sellers, the protagonists actually were girls. Griet in Chevalier’s Girl with the Pearl Earring is a 16-year-old servant who ground paint and later posed for her master, Johannes Vermeer. In House Girl, the slave Josephine is just 17 when she plans her escape from the tobacco farm. Lisbeth Salender, the brilliant, edgy protagonist in Stieg Larsson’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo series, is 24 years old, but is under guardianship, so she and her funds are under the control of Nils Bjurman, who viscously takes advantage of her. (Don’t worry, she gets him back big-time!)

In past “Girl” best sellers, the protagonists actually were girls. Griet in Chevalier’s Girl with the Pearl Earring is a 16-year-old servant who ground paint and later posed for her master, Johannes Vermeer. In House Girl, the slave Josephine is just 17 when she plans her escape from the tobacco farm. Lisbeth Salender, the brilliant, edgy protagonist in Stieg Larsson’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo series, is 24 years old, but is under guardianship, so she and her funds are under the control of Nils Bjurman, who viscously takes advantage of her. (Don’t worry, she gets him back big-time!) The twisted and downright wicked Amy Dunne in Gone Girl was followed by Girl on the Train’s protagonist Rachel Watson, a drunk and lonely woman. Both women are unreliable narrators because they are, well, crazy, and not exactly women to be admired.

The twisted and downright wicked Amy Dunne in Gone Girl was followed by Girl on the Train’s protagonist Rachel Watson, a drunk and lonely woman. Both women are unreliable narrators because they are, well, crazy, and not exactly women to be admired.